Why Your Team Stopped Experimenting

There’s a pattern I keep seeing in my coaching conversations with founders and team leads, and it’s one of those things that’s invisible until someone names it.

Here’s the setup: A leader rewards success. Publicly. Generously. Maybe it’s a shoutout in a team meeting, maybe it’s a bonus, maybe it’s a Whoop watch (yes, that happened). The intent is good. Celebrate wins, reinforce the right behavior.

But there’s a side effect nobody talks about.

Every time you reward success without equally acknowledging the cost of experimentation, you’re quietly extending the distance between failure and reward. You’re building a longer road. And the longer that road gets, the fewer people want to walk it.

I call this the Reward Distance Problem.

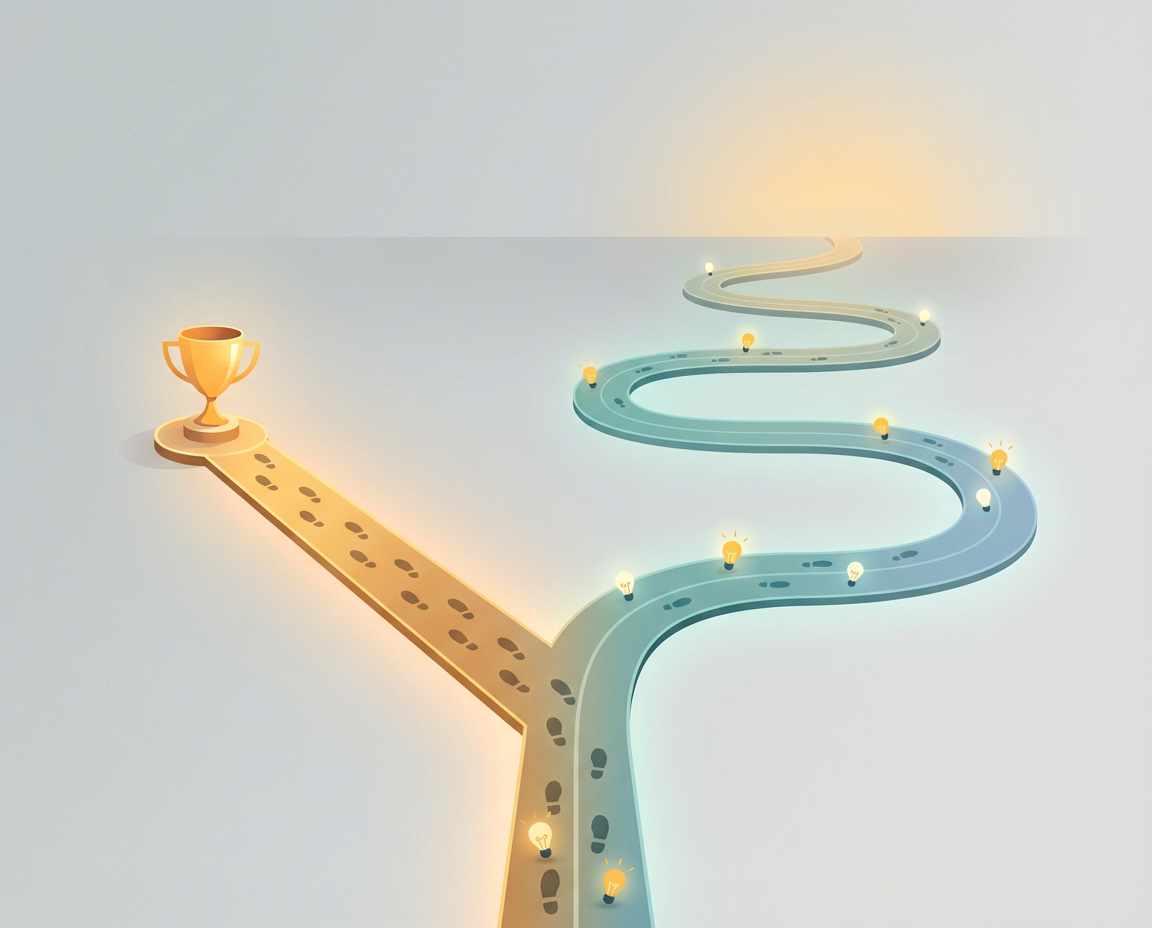

Think about it from the perspective of someone on your team. They see two paths in front of them.

Path A: Do the thing that’s known to work. Ship the campaign that looks like last quarter’s campaign. Use the tool everyone already uses. Stay in the safe zone. The reward is close. The road is short.

Path B: Try something new. Research it. Test it. Possibly spend two days on something that leads nowhere. The reward (if it comes at all) is far away, on the other side of uncertainty, dead ends, and the uncomfortable feeling of not knowing what you’re doing.

Now ask yourself: which path does your culture actually incentivize?

Most leaders I work with would say they want Path B. They want innovation. They want people who push boundaries and adopt new approaches. But their reward systems are quietly screaming Path A.

This becomes especially visible right now, as organizations try to integrate AI into their workflows.

A founder I was coaching recently described his frustration: “I keep telling the team to find ways to use AI in their work. I show them tools, I point them to possibilities. But they keep coming back with the same traditional approaches.”

When we unpacked it, the picture was clear. The team wasn’t resistant to AI. They were resistant to the risk of experimentation. Because in that company (like in most) spending two days exploring an automation tool that ultimately didn’t deliver would feel like two lost days. Not two days of learning. Two days of falling behind.

Nobody said that out loud. Nobody had to. The culture said it silently through what it celebrated and what it didn’t.

So what do you do about it?

The first instinct is usually to say “we should reward failure.” I don’t love that framing. People don’t want to be rewarded for failing. It feels patronizing. And it’s not accurate, you’re not rewarding the failure itself.

What need to be doing is shortening the distance between experimentation and recognition.

Here’s what that looks like in practice.

Change the language. “It didn’t work” is a conclusion. “We learned that this approach doesn’t give us the result we need” is a data point. This isn’t semantic games. When someone on your team hears “it didn’t work,” the emotional translation is “I failed.” When they hear “we learned,” the translation is “my effort produced something useful.” Words shape whether people feel like they’re on a dead-end road or a path that’s still going somewhere.

Make the learning visible. One of the most effective things I’ve seen a leader do is reference a failed experiment in a completely different context. In a meeting about a new project, he said: “We actually tried something similar. John wrote a detailed analysis of why it didn’t fit our needs. Let’s look at that before we go down the same road.” In that moment, the person who “failed” became the person who saved the team time. The learning had a second life. The distance to reward collapsed.

Measure experimentation, not just outcomes. This is harder to operationalize, and I won’t pretend it’s simple. But if the only metrics you track are conversion rates, revenue, and output, you’re telling people that the only thing that counts is the destination. The journey, the research, the testing, the dead ends that inform better decisions later becomes invisible labor. Find ways to make it count. Track experiments run. Document what was tried and what was learned. Create a shared knowledge base where negative results have a home.

There’s a deeper issue underneath all of this, and it’s the one I find myself returning to most often in coaching conversations.

When a leader says “my team won’t innovate,” what they usually mean is “my team won’t take risks.” And when a team won’t take risks, the question isn’t whether they’re capable. It’s whether the environment makes risk-taking rational.

People are remarkably good at reading incentive structures, even the unspoken ones. If success is celebrated and experimentation is tolerated, people will optimize for success and avoid experimentation. Tolerance isn’t enough. The road has to be shorter.

The Reward Distance Problem isn’t a people problem. It’s a design problem. And like most design problems, once you see it, you can start to fix it.

Daron Yondem advises senior technology leaders on AI-driven organizational transformation. Learn more →